My Favorite Artists

There are times when I have something to say about the artists I deeply admire.

- Adam Hughes

- Alessandro Barbucci

- Arthur De Pins

- Frank Quitely

- Katsuhiro Otomo

- Simon Bisley

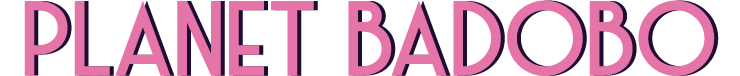

Herge

Georges Prosper RemiNotable works: The Adventures of Tintin

Growing up, I never "got into" reading because my mother was already doing so much of it with me. She remembered (I refer to her in the past tense as she's been shuffled of her mortal coil) delighting me with the hijinks of Archie and his friends. Their tightly written stories were always good for a laugh and a half. However, I distinctly recall being enraptured by one other comic series in particular - a series that has been and continues to influence me as an artist: The Adventures of Tintin.

Seeing as how this mini-essay is part of a collection dedicated to artists, I'll stick to singing praises for Herge's artworks. For the most part. But sing those praises I will. Anyone with even a passing interest in Franco-Belgian comics has undoubtedly come across his iconic art style known as ligne claire or "clear line." Herge didn't come up with the term (that distinction belongs to Dutch cartoonist Joost Swarte), but he definitely pioneered it. Strong, uniform lines portray characters and scenery; with another hallmark being vivid colors to distinguish the numerous elements from one another. The usage of such colors is necessitated by the absence of hatching to convey shadows. n

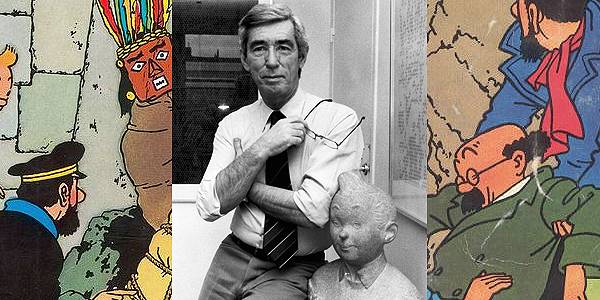

Practitioners of the style are all too familiar with how tricky it can get. A single misplaced detail could detract and distract, resulting in a muddled mess of an art piece. Yet Herge had no such problem by making his backgrounds and characters the polar opposites of each other. Allow me to explain in brief: Herge tends to draw his backgrounds as stark and lifeless, while his characters are anything but. You could pick and choose a panel from any of the pre-Tintin and Alph Art to see what I mean. But the stories that I think best embody this philosophy are Explorers on the Moon, Tintin in Tibet, and The Castafiore Emerald.

As the title suggests, Explorers on the Moon takes place on the earth's satellite. This means that at any point, Tintin and his crew are surrounded by an elaborate network of machinery within their rocket or the yawning vastness of the moon. Both present backdrops that are completely void of life. A deliberate choice as Herge opted to ground this revolutionary adventure[1] in reality and do away with the notion of aliens. Instead, there is nothing but a dark blanket of stars hovering above and the moon's rocky surface underneath their boots.

Returning to earth, Tintin in Tibet sees the intrepid boy reporter (and unwilling but ever-loyal ally, Captain Haddock) traverse across the massive emptiness of the snow-capped Himalayas. The duo plus Snowy brave avalanches, potential starvation, and precarious drops all to rescue his good friend Chang from a plane crash. Once they set out, almost nothing but pure white with the occasional mottling of brown is spread across a multitude of pages. Nary another soul is in sight. The oppressive feeling of loneliness one gets from reading through Tintin in Tibet never truly goes away. Even as more characters pop into the story to assist Tintin in his quest, including a particular cryptid of world renown.

Having concluded that harrowing enterprise. Tintin, Snowy, and the Captain retire to the lush opulence of Marlinspike Hall and stay there for the majority of The Castafiore Emerald. Captain Haddock becoming wheelchair-bound prevents them from going beyond the walls of his family's estate. So even as things escalate to boiling point- thanks largely to the overwhelming presence of famed opera singer, Bianca Castafiore - we the readers are trapped in a palatial yet fairly sterile chateau. If the Captain can't make a bid for freedom, then neither can we.

The moon, Tibet, and a country house. Herge illustrated all three as objectively as he could, sparing any fantastical components. On the other hand, characters are lovingly drawn with as much energy as needed in every panel they appear in, maybe even more in some cases. Herge excels in rendering physical comedy and human emotion onto comic pages. Instead of just falling down a series of steps, characters will end up crashing into the inside of a car and spill everything inside. A face normally absent of details will suddenly be contorted by wrinkles as they grimace through unbearable pain. Crowd shots will have so much happening that you'll need to take a moment to drink it all in.

That's how he's ensured that his art style never confuses anyone perusing through Tintin's 24 albums. His characters act as human as possible while his backgrounds remain static for the most part. It's these decisions that have made Herge's works so special and worth studying. Well, that and the gripping stories that continue to stand the test of time. But that's an essay for another day.

[1]Worth noting is the fact that Tintin stepped onto the moon in 1954 while Neil Armstrong wouldn't do the same until 1969. In other words, Tintin was the first man on the moon.

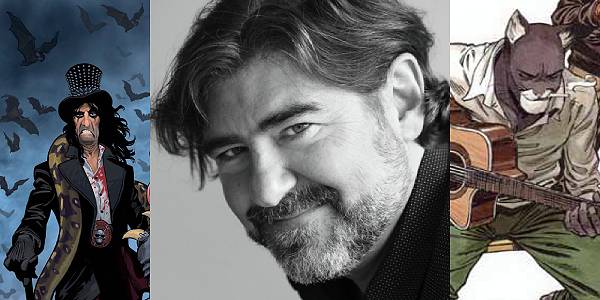

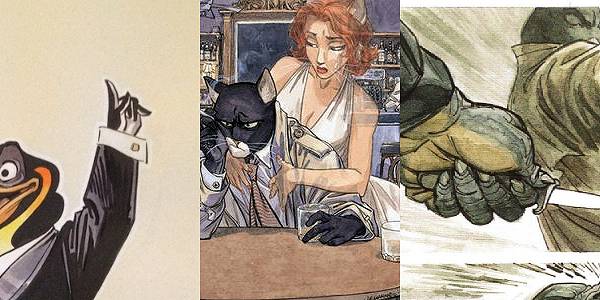

Juanjo Guarnido

Notable works: Blacksad, Freak of the Week

Having only one source of inspiration is nigh impossible for an artist. In our quest to become the best version of ourselves aesthetically, we'll cobble together a myriad of influences that can range from a solitary painting to a series of movies. For many such as myself, I tend to do the former: zone in on something that captures my attention so I can obsess over it like it were my One True Ring. That's essentially me with Juanjo Guarnido's hands.

The ones he draws, of course, and not his actual ones. Frankly, though, I wouldn't mind having them. If I did, I'd be creating magic every time I pointed a pencil at a piece of paper.

The artist behind the critically acclaimed noir comic series Blacksad, Juanjo Guarnido is no stranger to producing alluring visual feasts. Under Disney, he served as the lead animator for Sabor (Tarzan, Hades (Hercules), and finally, Helga Sinclair. (Atlantis: The Lost Empire) Once outside the company, he collaborated with fellow artist Juan Díaz Canales to co-create Blacksad.

He makes no mention of it but I'm certain his background in animation has taken his art up several notches. In addition to drawing justifiably hyperbolized poses and dramatic-when-necessary expressions, he makes sure his characters' hands are always up to something. A major key element to creating believable animation is to have it mirror real life. And unless we're asleep or dead, our hands are perpetually in motion, seldom immobile. Observe your hands at this moment. If you're hunched over a computer, your fingers are splayed above the keyboard. If you're on your phone, your fingers are curled over it with your thumb floating just above the touchscreen. If you're eating, your entire fist could conceivably be balled around some chips. As long as you're awake, your hands are gesturing, and that's what you'll see in Juanjo Guarnido's works. Hands pointing, gripping, relaxing, strumming, banging, snapping, picking, scooping, patting, scratching, and more.

Variety is also part and parcel of why I adore Juanjo Guarnido's hands. Grizzled old men have gnarled hands with skin stretched thin over protruding knuckles. Women of finer taste possess delicate fingers that end in impeccably manicured nails. Children paw at the air with chubby little mittens befitting their tender age. Even skeletons are given literally bony hands. Juanjo Guarnido does it all with a beaming confidence any artist should aspire towards.

Juanjo Guarnido is already a fantastic artist on his own. The care he puts into his hands makes him even better in my hands. If Milt Kahl is the ur example of how to draw hands for the screen, then this man is his equivalent for comics.